I just got back from India two weeks ago. INDIA! For those of you who have not been following the blog, I just finished staffing a gap-year program called Kivunim: New Directions. Kivunim seeks to explore Jewish history, and to that end travels to over 10 different countries to learn about different communities in the Jewish Diaspora. That’s right. I just went to India because there were and are Jewish communities there.

I can’t possibly tell you in one blog post everything that was India. So I’ll share one story with you. On our last day there we took a three hour bus ride from Mumbai to the small village of Panvel to see the Beit El synagogue of the Bene Israel community. The Bene Israel have been in India for thousands of years. The origins of the community are hard to pinpoint with historical evidence, but the legend and tradition is that they were part of the lost ten tribes of Israel who escaped Samaria in 722 BC, though some believe that they were sea traders who escaped the Galilee in 175 BC, prior to the events of Chanukah. Regardless, the story is that, the Bene Israel forefathers were shipwrecked on the Konkan coast, south of Mumbai, and proceeded to settle in the small villages there, where they became oil pressers.

The Bene Israel are said to be the only Jewish community never to have experienced anti-Semitism. They were fully integrated by their Indian neighbors, adopting their language, customs, and style of dress. Nonetheless, though outwardly indistinguishable from the non-Jewish Indians, they had a clearly distinguishable status and identity because of their Jewish observance. They were called Shanwar Telis, or “Shabbat-observing oilmen”, because they refused to work on the Sabbath. Isolated from the rest of the Jewish world for many years, the Bene Israel lost a lot of the liturgical and religious traditions, that is, until they once again made contact with other Jews around the 17th and 18th centuries. Nonetheless they always observed the Sabbath, circumcised their sons and celebrated the major festivals.

So there I was in the small town of Panvel. As with everywhere else we went in India, my senses were overwhelmed. I don’t think I know enough words to accurately describe what India is like. Even the most extreme poverty is distinguished by radiant colors. The streets are usually complete chaos. Crowds upon crowds of people, swerving cars and motorbikes, cows leisurely strolling down the dusty alleyways, incessant (and in my opinion useless) honking. Though Panvel is a small town by India’s standards, there was no shortage of people, colors, smells, and sounds. And right there, in the midst of this beautiful chaos, our bus stopped. We had arrived to the Beit El synagogue. Just visualize that image for a second. Two huge buses full of American 18 year olds and their cameras, sticking out like raisins in a bowl of peanuts, in this rural Indian village. Anyways, back to the synagogue. It was a small dirty facade, no different from the rest of the houses on the street, save for a small wooden Star of David at the top, which’s surface was enlivened by different color light bulbs.

The initial shock of there being a synagogue in that village, seemingly in the middle of nowhere, was nothing compared to the shock of seeing a community there! During the year, Kivunim became accustomed to visiting desolated synagogues, places that no longer housed an active Jewish life. In the back of my mind, I’d expected Panvel to be something of the sort. A place of ghosts, maintained maybe by an old Jew. But as soon as we passed the door, we were greeted by a community of around thirty people. Men, women, old people, small children. They were all gathered outside in the courtyard to celebrate the festival of Lag B’omer. They looked completeIy Indian, just like the people of the town. Same skin color, similar features, same dress. The only difference was that the men were all wearing kippot, and indeed some of the women had also placed napkins on their heads.

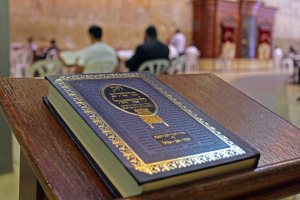

After the initial greeting, and after taking off our shoes, we were allowed to step into the synagogue. It was absolutely magical. Small and quaint, with little oil lamps hanging from the ceiling, and true to its Indian heritage, radiating with color. Deep, passionate reds, and vibrant yellows. After a few minutes of acquainting myself with the place, sitting down, and checking out some of the Hindi and Hebrew writings, I came across the most fascinating thing. Above the Torah ark, as in many other synagogues around the world, was an engraving of the Tablets of the Ten Commandments. Yet, they were not the domed rectangles I was used to, but two squares side by side! Let me explain why this was so fascinating…

Just the night before, Rabbi Dov, director of our program, had told us about the tradition behind the depiction of the Tablets of the Ten Commandments, one of the most salient symbols in the Jewish tradition. Apparently even though Talmudic sources describe the shape of the tablets as two squares side by side, in the vast majority of cases the tablets are depicted as two rectangles with arched domes at the top. The image of the arched rectangles, stems from the Roman and Christian traditions. The Romans, and later the medieval Catholic kingdoms would use the two leaves with curved tops as a kind of registrar, to list names of magistrates or of important people. The shape of the domed arch also became a mainstay of the Gothic architecture that characterized Christian Europe during the Middle Ages. Thus, one of the most recognizable symbols of our tradition is profoundly influenced by Christian civilization.

Every synagogue I have ever been to that depicts the tablets on its wall, shows them in the shape of the domed rectangles. Except the one in Panvel. Here I was, standing with Rabbi Dov in this tiny synagogue in the middle of India, and for the first time in both our lives we were seeing an image of the tablets that stayed true to the Talmudic interpretation; two squares side by side!

The tablets at Panvel epitomized one of the recurring themes throughout our travels. It highlighted the ability of the Jewish people to deeply immerse themselves in their surrounding culture, to adopt so many new ideas and practices, and yet still remain powerfully committed to maintaining their own cultural and intellectual heritage. Each community to its own extent, depending on the circumstances, developed a dual identity, on the one hand profoundly Jewish and on the other hand deeply embedded in the surrounding environment. The community in Panvel kept the traditional imagery of the tablets, but I was forced to take off my shoes before entering their place of worship.

I realized something funny this year. Every Jewish community from Morocco, to Germany, to India, seems to think of itself as representing the norm for Jewish life. Even my community in Colombia, a tiny one of maybe 3,000 people sees itself as the center of the Jewish world. Obviously nowadays we have the State of Israel, so everyone sees that as grand central. But usually that is it. It is Israel and your home community. Growing up, my conscience of a Jewish world extended mainly to Colombia and Israel. That was it. When I began to find out about Jews in places like Sweden, Morocco, Bulgaria, India, and even the United States to some extent, I saw them as exotic. I couldn’t believe that there were Jews in those countries. As if my identity as a Colombian Jew wasn’t a bizarre thing in and of itself.

What this implies is a profound ignorance of our history as a people. Nowadays most Jews’ knowledge of their history extends to the Holocaust and the formation of the State of Israel, with maybe a few Biblical stories and narratives to spice things up. Most Jews are unaware of the fascinating tales of the Jewish Diaspora. It is a unique history, one that tells not only the stories of Jews and their tradition, but gives us glimpses and insights into other great cultures and civilizations. Moroccan Jewish history is part of Moroccan history. Indian Jewish history is part of Indian history. German Jewish history is part of German history.

In many communities around the world, Judaism has become stale and dormant. People, especially young people, are less and less interested in exploring their Jewish identity. As we face the challenge of assimilation, as we seek to revitalize our culture and tradition, especially among the youth, we should delve into our diverse and fascinating history. It is in the chants of Indian Jews, in the philosophies of German Jews, in the music of Moroccan Jews, that we will find the tools to make Judaism funky.

To see the original source and author of this please go to this URL:

http://rejewvenator.com/?p=685